The central transformation of this book is to transform one’s world and self from an everyday way of being to a more open, responsive way of being: I call this a phenomenological transformation. Through this shift in our experience—in how we experience—we’re struck by things in their particularity. Things take on senses that don’t stem from us. Things reach out to us, show us their character, and stand forth from out of their world.

I explore this concept of “world,” for our responsivity must be engaged from out of our world and towards the worlds of others. Thus, I draw on Martin Heidegger, for whom humans are in a world, where world is: the totality of involvements, how meaning hangs together, and the set of pragmatic relations, all ultimately based on how beings are disclosed to us. In other words, our world is where beings are what they are.

But there isn’t just one world. First, there are different human worlds: historical and contemporaneous, for our world is not that of the ancient Greeks, nor that of contemporary indigenous Amazonian peoples.[1] Second, there are non-human worlds: animals, plants, and so on. Third, and more broadly, all beings have worlds, their own worlds—which are shared and distinct for each group of beings—for all things maintain themselves while opening beyond themselves—they maintain themselves while opening to all others, i.e., to beings as a whole. I call that which has this structure of maintaining and opening opening-while-holding-back.

In each case, worlds are where beings are what they are. They’re encompassing ways that all things are, ultimately not reconcilable to any one world or perspective. Nonetheless, and paradoxically, each world constantly reconciles and is reconciled by other worlds and ways of being. To understand this irreconcilable reconcilability, I draw on Canadian poet-philosopher Jan Zwicky’s ideas on metaphor.

Metaphors say X is the case while also implying that X is not the case (X is and is not Y). That is, metaphors gesture to the similarities between contexts (the ‘is’) while maintaining the essential distinctiveness of the contexts (the implied ‘is not’). In our society, we tend to notice the distinctiveness of things (which we take as separability or independence) and their similarity (which we take as the reductive identity or sameness of things): thus, we take things to be both independent and interchangeable. Contrarily, metaphors emphasize what is common between contexts while respecting their difference. Like a hinge that connects and separates things, metaphors first bring contexts and entities together and then allow them to return to their own contexts. Things are simultaneously dependent and unique: that is, dependently-independable.

How does metaphor help with the multiplicity of divergent worlds? By “metaphor,” I don’t mean something representational or linguistic, though metaphors are something we use in language. I mean something broader, for I’m interested in the structure of metaphor. Different worlds relate metaphorically. This doesn’t mean we represent this relation in consciousness; it means that the structure of how different worlds relate is the same as how a metaphor is structured.

There are different ontologies, ways of being, or worlds occupying the same space: though they share aspects in common, worlds are distinct. Because each wholly encompassing world opens its own way of being which overlaps with others(e.g., a bear’s world is not our world), I speak of metaphoric ontology. Metaphoric ontology describes how Being flashes out as distinct worlds that are interacting, irreconcilably reconcilably.

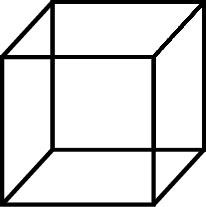

I delve further into this by drawing, as Zwicky does, on the Necker cube:

This gestalt figure is a cube that projects either upwards and to the right, or downwards and to the left. The Necker cube is a metaphor for being, which projects in different ways: i.e., as distinct, overlapping worlds. The Necker cube is another way to show the structure that underlies how different worlds relate; while the two projections of the cube share aspects in common, they are distinct. In other words, metaphors and the Necker cube are similarly structured, and I use both to gesture to the structure of distinct worlds.

Thus, with Zwicky, I caution against our societal tendency towards reductionism—insisting the cube is ultimately a set of lines we interpret—for reductionism focuses either on what is in common at the expense and collapse of difference or on difference at the expense and denial of commonality.

Likewise, though worlds are distinct and multiple, they do overlap, share aspects, and interact with one another. Every world is open to every other, and exists only because it’s open to others. The multiplicity of worlds finds a kind of unity in each distinct world; all worlds are shared worlds. This is how they’re irreconcilably reconcilable.

We glimpse other worlds from our world. For example, when we’re struck by a thing’s particular thisness, we may see how the world could be for it: we see the whole focused through this.[2] We glimpse a wisp of world, which is how worlds can appear in other worlds. An ontological transformation is to explicitly open oneself to the world of an other.

Because other beings are in one’s world, worlds are ongoing negotiations with others. At times, we can be inattentive, neglectful, or outright violent towards others. And yet, they strive for their own relations and, if we let them be (or even if we don’t), an auto-ontological transformation may occur: the uncovering of one’s own world and ways of relating. Before imposition on others, power is to be called by and placed into relations with things. Only secondarily does power function as imposition of one’s way of relating onto others.

Inattentiveness can be unintentional. To bring ourselves to an understanding of the multiplicity of worlds requires we transform ourselves and our world onto-theologically: on the level of principles of how beings appear and are gathered together in a world. In our tradition, we’re led by an ever-increasing reconciliation of being in our transition from Homeric gods to the Judeo-Christian God, who becomes replaced by the One. This is the principle of objective relation and the view from nowhere, and it informs atheism, science, multiculturalism, and managerialism. The One is the onto-theological reconciliation of all ways of being in a single unity. Thus, it hinders awareness of other worlds, for its reconciliation is based on reductions. Therefore, we need an onto-theological transformation.

In this book, our guiding thread is the phenomenological transformation—the transformation of our mode of being. This path is how we arrive at other transformations.

Transformation involves ethics: we attend to beings and their ways of being in the world; we enliven all beings and our relations to them. Thus, this is an enactive and practical philosophy.

This book is about the importance of attending to one’s attention; it broaches an ethics of attentiveness. It’s a mystery how and that we are called to beings.

[1] “Our” means ‘us’ in our group, in the Western tradition and in Canada or America, though I hope this book finds resonance outside this group.

[2] Jan Zwicky, Wisdom & Metaphor, 2nd ed. (Kentville, Nova Scotia: Gaspereau Press, 2003, 2008), LH53–5. Zwicky’s Wisdom & Metaphor is composed such that the left hand (LH) and right hand (RH) pages are given one page number (e.g., LH2 and RH2). The left-hand page of each spread consists of her writing, and the right-hand page consists of parts of works by others, which she has compiled and arranged.